Landscape-water

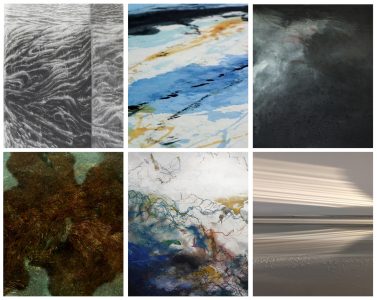

A cross cultural project: Landscape, or how to reconcile with nature

Having landscape as the theme for an exhibition means taking into account the current challenges posed by climate disruption and nature’s extravagances. We are forced to acknowledge that nature is unleashed just about everywhere in the world, forcing us to take it into consideration and reflect on our shared history with her.

Since the Renaissance, we in the West have developed a decisive axiology that enables us, through the combination of poles – technology, science and rationality – to channel and dominate nature. This modern anthropocentric attitude favored the development of a particular discourse that we are questioning today. It gave us the opportunity to set in motion a process of conquest, to appropriate nature and consider it as a reserve from which we have the right to draw. This relationship with the world has obviously become globalized, as it belongs to economic reason. Today, no one escapes it, nothing resists it, apart from a few climatic changes that are beginning to disturb us.

Artists, in turn, are part of this new awareness. Nature as “phusis” – that which grows by itself without human intervention – has been forgotten, even cursed or denied. If we agree to change our mindset towards nature, and are prepared to accept it as an inalienable partner, then a new axiology could be born.

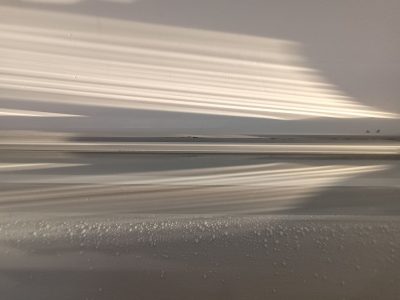

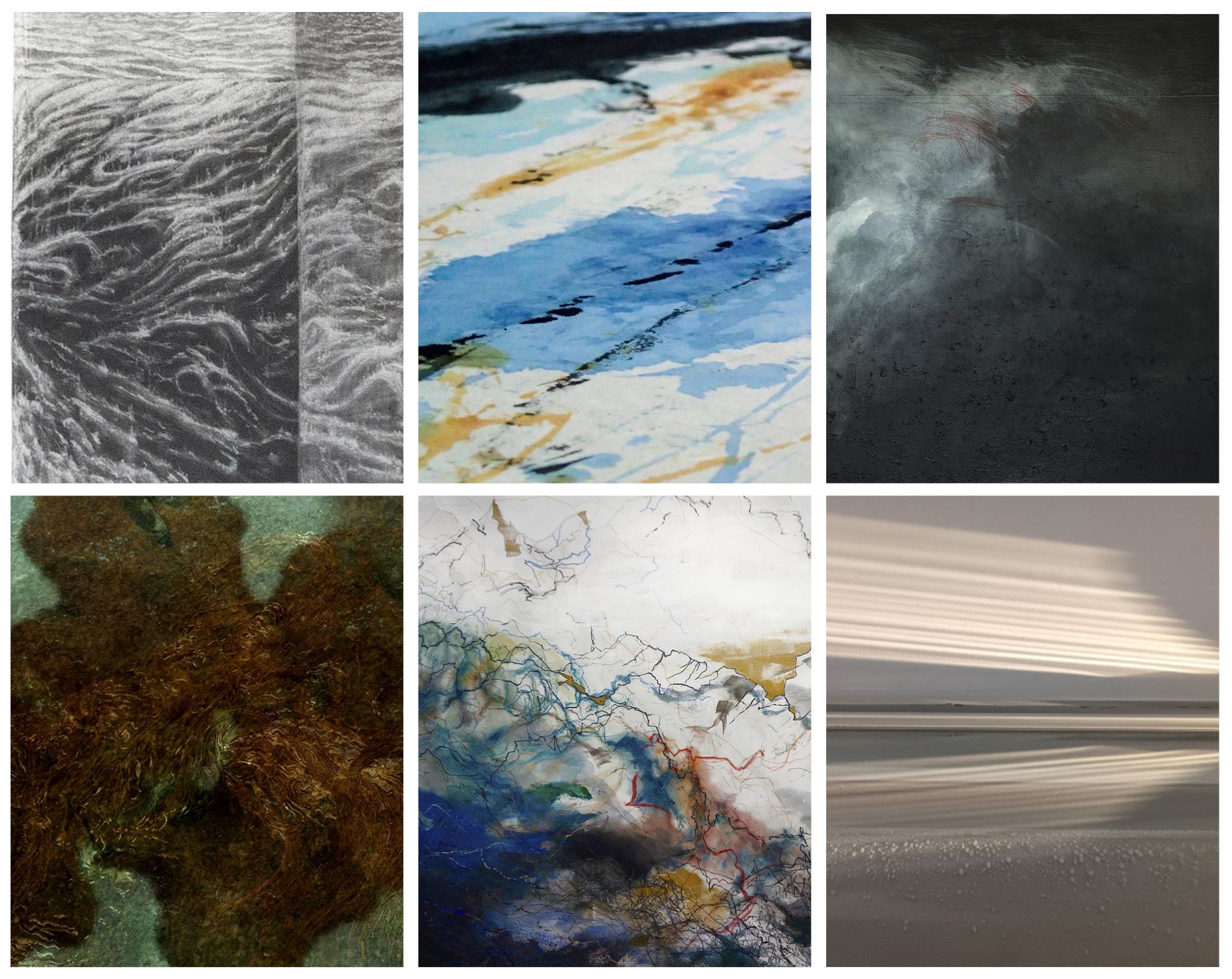

To start composing landscapes is to inaugurate a dialogue with nature, i.e. to open up to the powers of the living, to be receptive to the spontaneous rhythms, movements and energies that modern language has neglected and ousted.

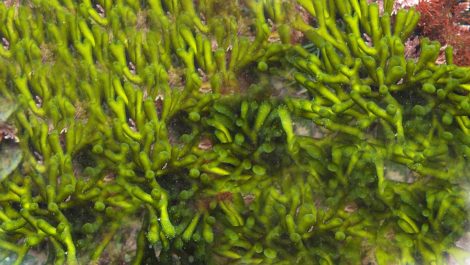

The landscape thus plays an essential role, bringing together fundamental components via animated paths traced by man in harmony with nature. Human and non-human paths harmonize in and through reciprocity, thanks to the median element, water.

For our part, in order to highlight the importance of landscape, we’ll start with traditional Chinese aesthetics. From the Tang dynasty (618-0-907), landscape became the focus of philosophy, painting, calligraphy and poetry. The brush, a means of expression for the learned, was used as a reserve of ink and water. It enables educated, civilized man to listen to the inner workings of things. Handling the brush encourages an inner search, and this alone enables man to associate himself with the original universe, the cosmos.

The expression par excellence of Chinese aesthetics, “mountain-water” assimilates the two fundamental elements of landscape painting.

Confucius said: “The man of the heart delights in the mountain, the man of the mind in the water. Here, then, are the two poles of human sensitivity that offer a similarity with nature. This microcosm-macrocosm relationship is intended to show that mountains and water are the main agents of universal transformation. It’s about reciprocal becoming, the perfect harmony of opposites and allies, mountain and water.

This reciprocal becoming implies a circular movement, which in turn implies a cosmic rhythm. This embrace is made possible by the presence of the void and the vital breaths that create open spaces through the atmospheric input of water-logged mists and clouds. These incessant relations between permanence and evanescence, or the masterful relationship between mountains made of rock and the nebulous waters formed by mists, give rise to rivers.

China’s age-old aesthetics enable man to join the breath of the cosmos and nature. Contrary to modern thinking, man has never been considered external and separate from his environment. Of course, mentalities have changed nowadays, but classical Chinese thought was nonetheless one of sustainable development, harmony and harmony with nature. Water invites us to follow its rhythm and share its energy. To follow its natural course is to embrace the path of dao, of non-action, or to block it with action.

Today, attempts to bring man closer to the world are multiplying. Landscape is part of this new eco-politics, which aims to reactivate our sense of belonging to nature, to its rhythm and cosmic energy.

The landscape-water exhibition will be organized around an initial focus on landscape from a contemporary Chinese point of view, by artist Peng Mei-Ling, professor of Chinese painting at IBHEC’s Musée du Cinquantenaire, who has been living in Belgium for several decades, and Finnish artist Anna-Maija Rissanen, who is completing her doctoral thesis on Chinese painting in Shanghai.

The second section will focus on contemporary issues concerning our environment, with research by Oliver Pestiaux, a philosopher, artist and researcher involved in an artistic eco-political approach. Secondly, the installation by Catherine Menoury and Christian Laval, equally committed to the new relationship between nature and culture.

The third focus will be on the work of Joseph Winckler and Teodora Cosman.