OPENING

FINISHING

Toriteri – l’être post-territoire

TORITERI is a new visual art production face and line. TORITERI is an inspired production of artworks, mirroring the appropriation of space as the singular expression of being, through the possible post-territorial and post-truth futures.

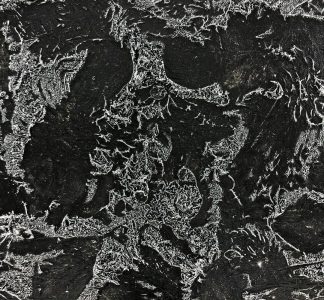

TORITERI embraces aleatory and repetitive forms. These forms resonate with phenomena observed in nature and cause the visitors to experience a paradoxical feeling of emptiness associated with plenitude.

Emptiness through fullness

In residence since the beginning of April, Hugo Bonamin and Liena Dyrbye Jensen have been working in the space entrusted to them.

Under the name of emprunt Toriteri, the two artists – one an architect, the other a painter – are conducting research that is at once experiential, physical and speculative into place as territory.

Taking as their starting point what has always mobilised us with the desire to conquer, the artists began by measuring the space and making a model of the place, which they took care to calibrate. In doing so, they were unable to avoid their emotions and feelings about a space they were beginning to understand through their own bodies. Letting the floor, its sounds and the walls come to meet them, they gave in to their tacit presence.

Their conception of the territory, which they initially occupied as residents, was transformed into a field of possibilities, metamorphosing the model into various flexible and formless elements that bring to mind the ‘body without organs’ of the philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. And the choice of the title “Toriteri” already reflects the desire to reterritorialise that these same philosophers have developed at length.

This is how the model of the place, having lost the rigidity of the units of measurement, became this body without organs that absorbed the light and the limits of the objects that became spatial corollaries. Toriteri disengages from territoriality to create new planes, lines and signs leading to the mystery of all things, namely the fundamental void, the vital flow.

“It’s like the emergence of another world. For these marks and features are irrational, involuntary, accidental, free, random. They are not representative, not illustrative, not narrative. But neither are they significant or meaningful: they are non-signifying features. They are features of sensation.

Here we are confronted with a relative relationship to the world that breaks with the rational stakes of representation, leading us to the other side of the stage and set. The relationship of scale subverts our memory, taking us from full to empty. Our memory,‘ Toriteri claims, ’saturated by all that it has absorbed in daily life, disengages from it to rediscover the generative force of the void.

In the same way, nothing is stable with the two artists, who are also offering a book of colours obtained by chance, involving the working of light and the cohabitation of two components.

Simone Schuiten

In the Land of the Post-Territorial Being

When I first encountered the large black canvases in the exhibition, my immediate reaction was to think of maps. Monochrome and vast, the surfaces appear at once impenetrable and legible; like aerial photographs of unfamiliar terrain, each mark a signal of elevation, rupture, or flow. Yet the longer one looks, the less territorial they seem. Instead of fixed boundaries or plotted coordinates, they evoke something more organic: a rhizomatic network, endlessly unfolding, more mycorrhizal than cartographic. These are not territories one can possess or even fully perceive; they continue, irrespective of the viewer, the frame, or the ground they supposedly represent.

At the heart of this exhibition is an interrogation of what it means to inhabit or claim space today; as artists, viewers, partners, citizens, or simply bodies moving through the world. The “post-territorial” here is not a negation of territory, but a reconfiguration: an acknowledgement that the structures and surfaces once used to contain or define identity, authorship, nationhood, and even art itself, no longer hold in the same way.

Relational Territories

Michel Houellebecq’s The Map and the Territory (2010) famously reanimates Alfred Korzybski’s assertion: “The map is not the territory” (1933). Representations of the world, whether maps, narratives, or aesthetic forms, are never neutral. They are shaped by ideology, infrastructure, and intention. The artworks in this exhibition engage with this slippage, exposing the persistent gap between representation and lived experience.

In one case, a sculptural form appears to block visual access to a large part of the exhibition space: a vast, swollen black volume, reminiscent of a gigantic bin bag. It is simultaneously absurd and monumental; a banal object made uncanny by scale and context. Originally designed to conceal a piano that disrupted the visual narrative, it now dominates the room. But who decides what should be visible or hidden? Who, in this space, defines the perimeter?

Here, territory becomes a question not only of place, but of power.

This becomes further complicated in the collaborative work of Toriteri, the artistic duo at the centre of the exhibition. More than a joint practice, theirs is a life shared between Hugo Bonamin and Linea Dyrbye Jensen: as artists, co-parents, and co-inhabitants. In this sense, the territory of their work is never just conceptual or physical but rather domestic, emotional, and ethical.

Their pieces are iterative and open-ended, mirroring the continuous negotiation that defines shared life. There are no clean divisions between roles (researcher, caregiver, artist, architect, author, technician) just as there are no clean lines within their work. The very idea of authorship, often territorial by nature, is displaced in favour of exchange, intimacy, and risk. In their practice, territory is neither ceded nor claimed but held, momentarily, in common.

This approach resonates with Nicolas Bourriaud’s notion of Relational Aesthetics (1998), which places human relations and social context at the core of artistic production. Rather than creating autonomous, commodifiable objects, artists working relationally set up micro-situations; ephemeral encounters that are co-authored with their audiences. Toriteri’s collaborative methods and porous boundaries echo this practice, shifting emphasis from possession to participation, from mastery to mutuality.

This mode of working also extends to the broader collaboration behind the projection in the show, developed with students from ERG (École de Recherche Graphique), who did not know what they were working toward when they began. The process, like the result, resists containment. Here again, we move from the authoritative territory of the finished work to the shared, unstable terrain of co-creation.

The Territory That Moves in the Era of Disordered Attention

Claire Bishop, in her recent writings on contemporary spectatorship, argues that we now live in a condition of disordered attention (2024), fragmented by screens, notifications, and the algorithmic pulse of the digital. The gallery visitor, no longer fully anchored in physical space, shifts continuously between zones: the white cube and the phone screen, the reflective act of viewing and the distracted swipe.

In this sense, the post-territorial being is not only physically unmoored, but cognitively dispersed, shaped as much by invisible systems of data and distraction as by the (material) architectural space of the exhibition. Here, materiality returns with new urgency: the solid, tangible presence of objects reminds us that art, like territory, can still assert form and friction. These objects are anything but simple. Surfaces that at first appear flat reveal themselves to be the result of meticulous attention; layers of gesture, resistance, care. In the age of the instantly rendered, the slow labour of making becomes an act of insistence.

The exhibition also invokes territory as choreography: a matter of movement, rhythm, and return. From T.S. Eliot’s famous verses:

“We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time” (1943),

we are reminded that place is not static. It transforms as we do.

In this way, the circle that is projected on the wall becomes a recurring pattern, both in visual form and conceptual logic. Like the black sculptural volume attempting to hold a piano within a pre-defined shape, the exhibition explores what happens when form resists its frame. What happens when the place we return to is no longer the same? Or when we realise it never was?

Post-territory is not a future state, but a present condition. A way of seeing the world not through borders, but through relations. Not as possession, but as presence. It is a world in which meaning is made through movement, not settlement, and through tracing, not enclosing.

Territories of Exhibiting

Finally, we are left asking: what is the territory of art itself? In this beautiful, cared-for space with high ceilings, elaborate decorative details, and solid wooden doors, what does it mean to place a form that refuses elegance? And then another that celebrates it through meticulous craft and painterly detail? What does it mean to allow strangeness to intervene in the canonical expectations of gallery display?

The exhibition does not offer clear answers, nor does it map a new territory in any definitive sense. Instead, it gestures toward the multiplicity of ways in which we might rethink our relationship to space, to others, and to the act of making. In a world where territorial lines are increasingly unstable, it invites us to consider what lies beyond them.

What would it mean to occupy, even briefly, a post-territorial position?

Perhaps it begins here: with the black surface that holds no coordinates, the rhizomatic black canvases, the circle that escapes its frame, the collaboration that refuses hierarchy. The post-territorial is not a destination, but a practice; one of attention, disruption, and care.

Elena Papadaki

Associate professor in Curation and Digital arts, University of Greenwich (UK), ERG (BE)

Associate Curator

——–

Claire BISHOP, Disordered Attention : How We Look at Art and Performance Today, Verso, 2024

Nicolas BOURRIAUD, Esthétique Relationnelle, Les presses du réel, 1998

Michel HOUELLEBECQ, La Carte et le Territoire, Flammarion, 2010

T.S. ELIOT, Four Quartets, Faber and Faber, 1943