Li Bangyao, the Pop Art sociologist

Simone Schuiten et Xiaoman Li

Born in Wuhan, Hubei province, in 1954 – a period of time when access to paper and pen was still limited – Li Bangyao liked to paint on the ground with a piece of chalk during his childhood. His open-minded parents never stopped him, and ensured a tolerant and independent space in which Li Bangyao could make his choices freely.

In the late 1970s, Li Bangyao entered the Hubei Academy of Fine Arts. Although he always wanted to study oil painting, he was assigned to the graphic design department. This accidental academic development laid the foundation and influenced the tone of his later creative work. His oil paintings, in a way, are at odds with the traditional way of painting. Perhaps, it was his intention to do so in the first place, given his rebellious and uncertain character.

In the 70s, education resources in China were scarce. The number of painting books available was limited and mainly related to the Soviet Union. It was only after 1978 that Li Bangyao had a real chance to get into contact with Western art works. This first encounter with Western works opened up Li Bangyao’s curiosity towards the world of Western arts. He started to spend a lot of time reading the history of impressionist painting.

At the same time, the Chinese painting movement started to show a non-realistic upsurge. In 1979, a number of artist unions emerged during the “Beijing New Year Landscape Painting Exhibition”, “Unknown Painting Association” and “Star Art Exhibition”. Established and young artists gathered in a voluntary and collective way. Their artistic style represented the experimental modernist wave in China. These artists reflected on the “Cultural Revolution”, and also reflected on the traditional Chinese culture, that is to say, Confucianism. A common question was whether Confucianism could continue to provide the main guidance to, and remain the core of, China’s modern cultural system. This questioning not only implied changes to the Chinese art system, but also foreshadowed changes to the entire social system.

Thanks to his outstanding academic achievements, Li Bangyao was assigned to stay in school and work as a teacher after graduating from university. From then on, he officially began to create his own art works. In the early 1980s, he came into contact with western philosophies such as Sartre’s existentialism, Nietzsche’s life philosophy and Freud’s psychoanalysis theory. The contrast between light and shadow within the Western impressionism and the treachery of surrealism opened his eyes even more. Against this background, Li Bangyao carried out a variety of artistic attempts.

His eclectic art works have been loved by many colleagues and students, but at the same time, they have also attracted quite some criticism from his predecessors. In the eyes of the older generation of teachers, his works had limited artistic value, and was seen as simply unreasonable scribbling. Li Bangyao justifies his different perspective: “Western philosophy has taught me two key things: doubt and criticism.” At that time, Li Bangyao worked as lecturer for color basics, and he began to question what character color should be and how the course should be taught to students.

The 1980s witnessed the first decade of China’s reform and opening up, and Li Bangyao spent ten years reading Western art history and Western philosophy. The “invasion” of Western culture in those days has filled artists’ cravings for new things – like spiritual food. A large number of artists have turned their attention to the complex relationship between art, culture and life. Under the influence of Duchamp and Rauschenberg, the wall between art and life has been tore down, and daily consumers’ merchandises have entered artistic creation in an unprecedented way. In 1985, various newspapers and periodicals (such as “Art”, “Art Trend of Thoughts” and “Chinese Arts Daily”) covered at length this new artistic development in China, and its humanist spirit.

In just two years time, more than 70 youth art groups have been set up in 23 provinces and regions across the country. Li Bangyao took root in the “Tribe of Hubei”. Although it only existed for few years, the two exhibitions of the group in the 85s caused a lot of sensation within the Chinese art world at that time. It can even be said that the 85s New Wave was like a hasty and immature rebel movement in adolescence. It was filled with enthusiasm and energy and thus meant that it had to be transitory.

When did Li Bangyao’s obsession with “objects” begin? In the 1990s, fundamental economic changes took place in China. With increasing marketization, a large number of Western commodities entered the Chinese market and fascinated Chinese consumers. Such materialistic market landscape made Li Bangyao think thoroughly about the concept of “object”. In a way, the concept of “object” at that time was multi-faceted. What mattered was not only the “object” itself, but also the thinking of “material” and “the desire for material”.

In 1992, Li Bangyao was transferred to the Fine Arts Department of the South China Normal University in Guangzhou. In the same year, he created his first series related to the theme of object (entitled “Product Trusts”). In this series of work, he listed 20 to 30 items of daily necessities, varied from large to small ones. The work ironically revealed the truth of the dazzling Chinese consumer culture by highlighting the flat and monotonous nature of consumerism.

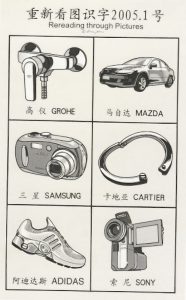

From 1993 to 2007, he created several other important series, such as “Memory Fragments”, “Models”, “Words and Objects”, “Re-Reading Pictures”, “The Origin of Species” and “Evolution”. With these works, he paid increasing attention to the contextual problems of objects. According to Li Bangyao, “there can be no communication without contexts and symbols of language”. Not only young children have to learn how to communicate and establish the context for communication, the understanding of “object” is also a strange and long process for adults.

Meanwhile, “the core of art should involve social issues, otherwise it can’t be called art.” Li Bangyao’s concept of “object” is rooted in the oriental culture. “At that time, I really wanted to keep distance from the Western influence, to find out about the problems of my own country”, he says. Therefore, his concern for commodities in industrial manufacturing and the reflection on the social problems arising there from can often be seen in a great number of his art works. Simultaneously, Li Bangyao has also reconsidered and wisely integrated the Western Pop culture into his own works.

In 2000, Li Bangyao studied the work of the French philosopher Baudrillard on “The System of Objects” and “Consumer Society”. The artist’s obsession with “object” found new theoretical support and enabled him to logically think the concept of “object”.

For Li Bangyao, the objects he studied after 2009 are different from those in the previous consumers’ society. In the past, items focused on their own symbolic nature in consumption, but nowadays, they mostly focus on their function and their owners, that is to say, their social attributes. Following Baudrillard, in the past, the objects which functioned as the system of communication and exchange were “a symbolic code which is continuously sent, received and recreated. It is also a language”. From 2009, Li Bangyao has brought the concepts of objects into the family context, focusing on their social significance, and their special connection with people.

Looking for the Commonplace

In 2018, Li Bangyao exhibited his “Indoor” series at the ODRADEK Gallery in Brussels, showcasing a series of the evolution of Chinese interior spaces in a Western gallery, from the years 60 until today. During a three-month period, Li Bangyao recorded interviews with Western families, and brought the items of several families back to China. He explored the structure of the house, the furnishings of the room and the obvious and less obvious characteristics of the owner, as if he was treasure hunting. Apparently, it is also an adventure to explore a private world.

The exhibition on “Looking for the Commonplace” (Redtory Factory, Guangzhou, June 2019) is Li Bangyao’s summary of the past decade. Li Bangyao adopts a variety of forms to present the objects used in families as objectively and figuratively as possible. The exhibition combines visual art, installation art and graphic art. In this process, Li Bangyao tries to maintain a rational distance from his own works and objectively present the significance of objects in families.

Li Bangyao decided to exhibit both his own creation and the interviews he has conducted over the years. Thanks to the vast space at the Redtory Art + Design Factory, Li Bangyao presents the “objects” he collected by assembling them into a large facade, and combining them with video materials. We have the privilege of visiting Li Bangyao’s studio many times when he was preparing his works, and we have witnessed these works transforming from electronic images on the screen to flat models and finally to three dimensional objects. Inspired by folding books for children, these devices can be folded into a two-dimensional plane – a technique that reflects his early education as a graphic designer. He says, “The same is true for families, every family could be folded up like a book.” In his studio, the huge objects were often surrounded by seven or eight students, who used knives to carve the lines on the aluminum plate into the shape of the objects, day after day for months. Li Bangyao sometimes joked around and said: “Without these little ‘robots’, I would never finish the project.”

To help answer the possible confusion of the audience, Li Bangyao uses interviews and videos that provide the host’s point of view. By combining these images and the information they convey with the graphic works themselves, the artist offers to the viewer a unique visual experience and perception.

Furthermore, Li Bangyao has arranged these objects into “families”. The idea of “family”, as well as family space and objects, attracts much attention, especially in oriental society. The choice of furniture, the orientation of the house and the interior decoration are closely related to the family members. With the commercialization and privatization of living space, it has become people’s property. The once harmonious and quiet domestic space gradually succumbed to the market economy, and can even lead, according to Wang Min’an, to “residential politics and spatial politics”. Compared with the past, the family home is no longer a warm and readily available living environment. A home’s interior decoration, size, geographical location and environment are directly associated to happiness. The internal family space breeds social and ethical relations, while the external family space is related to the social relations between production and reproduction.

That is to say, the function of furniture and object is first and foremost the embodiment of human relations, to live in a shared space, and even to have a soul. The “sense of presence” of each item is what Li Bangyao wants to express. It has to have a soul, and to make a connection with people. One has to watch it move alive. One may say that the object itself has no emotion, but it is able to collect people’s living memories, anxieties or joy, which is why it is said “to belong to us”. All of these come from “consumption “, or we say, an exchange of emotions and values. In this way, all the functions of items can be rationalized. It is open, it has no attributes. It’s about time, it’s about human activity, and that’s all.

Li Bangyao’s research on “object” will continue. The entering of the family in the Western world is the first step in his study of “object” across cultural differences, which is also the most important step. Art has no borders, and Li Bangyao does not like to talk directly about the differences between the East and the West. His current focus is on the reflection of objects on cultural patterns of different strata and their spiritual pursuits. He seems to be looking for the “Aura” which object have by nature, following Walter Benjamin’s theory on the era of mechanical reproduction. Li Bangyao is using a mechanical way to guide people to feel the life of object. From this point of view, he is sometimes ambiguous. Most likely, interviews with different families will remain his main way of research. Li Bangyao knows very well that only by collecting abundant samples, his work will be even more persuasive. One can imagine the future exhibitions will look for more uncommon in the commonplace.

The Strange Power of Objects

Following the theories of the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard – who compares the world of the objects surrounding us with the vegetal or animal worlds- Li Bangyao methodically, describes the objects supposed to enhance our life. The function and utility of the objects seem to have acquired a new status: a sovereign presence in society. Everyday objects have become veritable “phenomena” which, when numerously reproduced, engender new life-styles, new ways of existing. It is our life with these objects that Li Bangyao stages in his work. He emphasizes the close bond that contemporary society maintains with his auxiliaries such as our watches, cars and various accessories. This general approach emerged in Europe and was represented by the Pop Art movement. Artists such as Andy Warhol highlighted the phenomenon of standardization and endless reproduction of consumer objects, i.e the fact that factories are able to massively produce goods supposed to increase our wellbeing.

Jean Baudrillard in “The System of Objects” and in “Consumer Society” analyses the changes operated in our societies, based on the relationship consumers have with their objects. He endeavors to understand why and how contemporary society establishes specific relations with objects.

Li Bangyao’s work takes us to two different paths: one is China and the West’s mutual influences, or transfer phenomenon, and the other is the strange power objects hold on humans.

In the 1980s, astonished Chinese artists realized that a personal, individual or even singular approach out of the official and traditional canons was possible. They formed an avant-garde and became very active adopting Western movements such as Impressionism, Dadaism or Surrealism. In the context of the 1980s, the notion of transfer can be understood as follows, in this overhauled era inaugurated by Den Xiaoping, society as a whole and more particularly artists, consciously or subconsciously resorted to new tools in order to understand and respond to changes.

The new-found freedom of Chinese artists to choose their way of live and of thinking drove them to adapt and stimulate their imagination, in a genuine and creative way. It was for them a fascinating encounter with the new aesthetic investigations brought about by Western art. This is why transfer is definite as a period of transition-adaptation and deep assimilation of new parameters.

This process could be understood by some as a contamination effect. To others transfer is enriching and evidence of a successful “cross-cultural” encounter. Li Bangyaos’ work is living proof of an authentic and well thought out synergy.

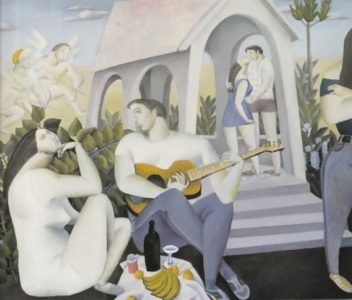

It is necessary to realize the extreme intellectual excitement artists felt for the colors, light, shapes and perspectives found in Western painting. Let us take for example “Lunch on the grass” by Manet. This amazing piece of work ostentatiously highlighted Western painting’s favorite model: the human figure and precisely the female figure. Li Bangyao took the same references to play with Western modernity. After having worked on human figures he, still hungry for more discoveries, focused his attention on his main concern: the object. It is at that precise moment, when he gave up the human figure in favor of the galaxy of objects, that Li Bangyao joined the Political Pop Art movement which was thriving in Wuhan.

Li Bangyao doesn’t create his art from scratch, but he reproduces what he sees. His genius is in the interpretation coming from his visual and intellectual analysis as he remains astounded what he calls “New Materialism”. Without forgetting his sociological-phenomenological mission, Li Bangyao keeps describing the evolution of objects gravitating within the new Chinese culture.

The angle he chooses to develop completely differs from the scholars’ traditional aesthetic criteria. All that makes the magnificence of classical aesthetics is simply absent. Objects are represented by flashy colors when he does use color. His work is often only composed of grey color, and yet, the visual impact is remarkable and highly significant. It looks as though, in Li Bangyao’s critical eye, our daily world changes into merely stereotyped images. The viewer feels the strange impression of belonging to a frozen world where communication is extremely limited. People themselves, then seem to have become a desirable or enviable object.

Li Bangyao compares himself to Darwin and his theory of species. He too proposes a thoroughly imaged study of the evolution of objects belonging to the so-called consumer species. Paying homage to Darwin, Li Bangyao created a series of works titled “the origin of species” proposing a humorious and impertinent study on the essence of the said new species. His investigation method is visual, the objects he depicts are oversized and provocative as in advertising campaigns. Actually, the artist clearly discloses that scattered attention only registers the environment subconsciously.

This brings us back to the transfer process now criticized by Li Bangyao. Through his own visual language he demonstrates how society can let itself be influenced by the new species of objects. In this case, the transfer is considered negative as society is trapped by the power of branded objects. This very explicit transfer shows -to those who want to see it- the transformation and radical change of our way of life. Society has embraced a new species of objects and accepted its domination without ever truly realizing the transformations operated in us.

No panic though, Li Bangyao’s humour, poetry, cheekiness and brilliant wits make us aware of the trap. In this way, he gives us the opportunity of a successful transfer in the sense that we now have the means to face our daily life with more subtlety.

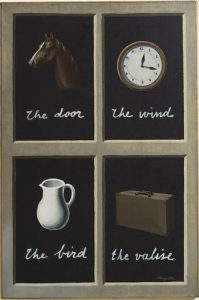

With respect to the phenomenon of intercultural experiences, the encounter between Li Bangyao and Belgian surrealist painting is notable. René Magritte is undeniably a precursor in the field of improbable combinations between words and objects, words and images. This mischievous and at the same time deeply philosophical state of mind corresponds to the Chinese mentality. There have been long-standing links and similarities between China and Belgium, and already the Taoists revealed how little reality there is in reality, and mocked it. Magritte, as a painter and philosopher, also highlighted the inadequacy between language and what it designates. The impact and visual strength of the images of his paintings reveals the great efficiency of graphic communication. The main challenge of his paintings is based on the pre-assumptions of our system of representation. The way he treats this issue is somewhat Chinese taking into account that he proceeds as a fine strategist.

Magritte stages logically impossible situations and thus provokes perplexity about what we think we know well. He has had and keeps having a great success with large audiences who appreciate his strange associations. To some extent, surrealism reveals the unusual imaginary world that sleeps in us. An exaggerated, out-of-standard and totally irrational approach to everyday reality is then appearing. Since this approach belongs to the field of art, we consider it compatible with our reasonable world. Many have fun with Magritte, some feel a certain discomfort because they get caught up in the game of destruction of representation.

This is precisely the common point between the Belgian surrealist and Li Bangyao. The Chinese Pop artist uses the tools of the surreal approach to highlight the power of contemporary objects.

The pervasive universe of consumer goods reveals, through the interpretation of Li Bangyao, the new obsessions of contemporary society. Magritte has created unusual situations by associating incompatible terms. Li Bangyao instead uses our familiar objects in their ordinary context and creates trivial and familiar, habitual, normal situations that unmask, indicate, detect, exhibit the surreal dimension of our existence. It is therefore by the intervention of the artist that facts and behaviors of society are unmasked.

From 2010 onwards, Li Bangyao has taken a turning point by making videos, becoming a sociologist artist. His approach is also philosophical because through the image he describes and observes how the object lives as a member and partner of a family. Today, objects play an essential role. Li Bangyao stages the way they are treated because he believes in their magical power. In each society as in each family, the relationship to objects differs. Accompanied by his wife, and equipped with their cameras, Li Bangyao therefore enters into Chinese dwellings to interview, film and record the surroundings and family life of the object.

We can understand his undertaking in the following way: as soon as he enters the universe of the family he will encounter, his mischievous gaze seeks contact with the objects. He must understand the system of objects that the family has developed, in other words understand the significance that the occupants of the premises have attributed to their “partners”. In this sense, Li Bangyao performs a real fieldwork. Already presented as a sociological researcher, he goes around the dwellings while taking pictures. This is how Li Bangyao gets acquainted with, meets with and enters into the intimate and particular world of a contemporary living space. All his photos are digitally reprocessed and resized. We can observe that our artist-sociologist-phenomenologist uses several filters while referring to and describing the world of contemporary objects. The first filter is of course his own eyes and his mischievous look, then the cameras that shoot pictures and videos and finally the sound recording. So many successive framings that allow him to create the necessary and sufficient gap between his own feelings and his objective target.

Li Bangyao pretends to be himself an object maker in the sense that he reproduces images through computer processing, which acquire a new dimension. He then gives an aesthetic and critical life to this little world that he observed during his family encounters.

Li Bangyao therefore operates by reducing and transforming objects that are familiar to us. Using computer technology, he manages to create special effects, i.e. a transition from the second dimension to the third dimension. That’s why we will fully focus on this “passage.” The first part of our analysis revealed the change that occurred to objects once they became part of our so-called consumerist lifestyle. Here they are, re-ritualized and celebrated by means of an artistic viewpoint. Li Bangyao oversized them in his own way. In fact, what he creates is nothing but the realization of the power we confer to the object. The artist stages our alienation from the object of our desires and the resulting fusion of subject and object. Just as “savages” had animist relations with nature, postmodern “civilized” people maintain a fusional relationship with their objects. Already Mr. Duchamp and R. Rauschenberg had focused on the everyday object, now Li Bangyao goes further by developing an aesthetic of illusion. During his exhibition “Looking for the common place” in Guangzhou, he proposed an approach that took us into the everyday world of our objects. Through his in-depth surveys of families from different cultural backgrounds, Li Bangyao no longer presents himself as an anthropologist artist but rather as a “voyeur” artist who has entered the intimacy of families. The private spaces he visited bear witness to a very active emotional sequence which we can visualize. The theatrical staging makes us become aware, in an amplified and climactic way, of our most familiar environment. We then discover that the objects around us function as friends, accomplices of our dearest desires.

Formerly, in China, ‘companions of eternity’ were put in tombs to escort the deceased. These statuettes or familiar objects were intended to distract and watch over the dead whose tomb they were keeping. Today, it is life, here and now, that we celebrate. That’s why the objects discovered by our anthropologist of everyday life reveal the energy released by the objects and the dynamics of the heart that animates their owner. We are not enough aware of the emotional value with which we have vested our objects. They can now be defined as the warm companions of our “inner” life.

We are once again confronted to a practice of exchanges and interaction between, on the one hand, the discoveries of the artist during his visit in Belgium and, on the other hand, the result of his creativity. It is a particularly successful example of intercultural transfer.

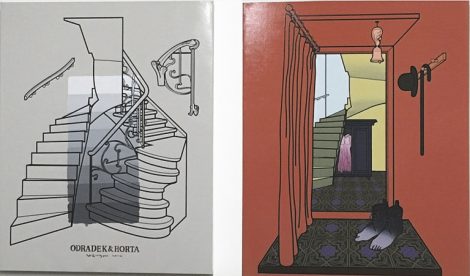

Li Bangyao continued his investigations by visiting numerous museums, including the Horta Museum located next to the ODRADEK gallery where he stayed. He then had the idea to create a surreal dialogue between the two places and composed two mutually corresponding works.

In the future, we are eager to follow new ventures from the Pop Art Sociologis Fig. 3 : Product Trust, 1992, oil on linen, 238 x 183cm

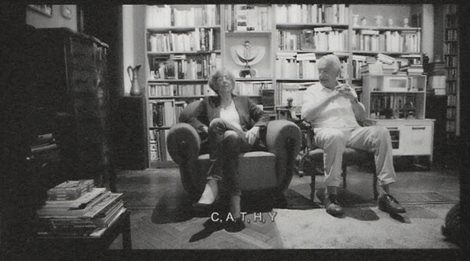

Exhibition INDOOR, 2018, ODRADEK, Bruxelles

Product Trust, 1992, oil on linen, 238 x 183cm

Exhibition INDOOR, 2018, ODRADEK, Bruxelles

Looking for the Commonplace, 2019, Redtory Factory, Guangzhou, Interview in Brussels

Fig 11: The Origin of Species, , 2006, acrylic on canvas, 146 x 114 cm

Fig 11: The Origin of Species, , 2006, acrylic on canvas, 146 x 114 cm

Lunch on the Grass, MANET Edouart, 1863, oil on canvas, 207 x 265 cm

Concerto without Lang Ya Grass, 1986, oil on canvas, 130 x 100 cm, in LI Bangyao, HEBEI FINE ARTS PUSBLISHING HOUSE, 2008

MAGRITTE René, 1930, The Key to dream

Rereading through, Pictures N0.1, 2005, acrylic on linen, 150 x 94 cm, in LI Bangyao, HEBEI FINE ARTS PUSBLISHING HOUSE. 2008

ODRADEK and HORTA, 2018, acrylic on canvas, 80 x 60 cm

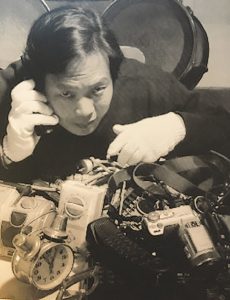

Artist photograph in Li Bangyao, Heibei Fine Arts Publishing House, 2008, p. 244